- Home

- E. B. White

The Elements of Style Page 2

The Elements of Style Read online

Page 2

In the English classes of today, "the little book" is surrounded by longer, lower textbooks—books with permissive steering and automatic transitions. Perhaps the book has become something of a curiosity. To me, it still seems to maintain its original poise, standing, in a drafty time, erect, resolute, and assured. I still find the Strunkian wisdom a comfort, the Strunkian humor a delight, and the Strunkian attitude toward right-and-wrong a blessing undisguised.

E. B. White

* * *

I> - Elementary Rules of Usage

1. Form the possessive singular of nouns by adding 's.

Follow this rule whatever the final consonant. Thus write,

Charles's friend

Burns's poems

the witch's malice

Exceptions are the possessives of ancient proper names ending in -es and -is, the possessive Jesus', and such forms as for conscience' sake, for righteousness' sake. But such forms as Moses' Laws, Isis' temple are commonly replaced by the

laws of Moses

the temple of Isis

The pronominal possessives hers, its, theirs, yours, and ours have no apostrophe. Indefinite pronouns, however, use the apostrophe to show possession.

ones rights

somebody else's umbrella

A common error is to write it's for its, or vice versa. The first is a contraction, meaning "it is." The second is a possessive.

It's a wise dog that scratches its own fleas.

2. In a series of three or more terms with a single conjunction, use a comma after each term except the last.

Thus write,

red, white, and blue

gold, silver, or copper

He opened the letter, read it, and made a note of its contents.

This comma is often referred to as the "serial" comma.

In the names of business firms the last comma is usually omitted. Follow the usage of the individual firm.

Little, Brown and Company

Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette

3. Enclose parenthetic expressions between commas.

The best way to see a country, unless you are pressed for time, is to travel on foot.

This rule is difficult to apply; it is frequently hard to decide whether a single word, such as however, or a brief phrase is or is not parenthetic. If the interruption to the flow of the sentence is but slight, the commas may be safely omitted. But whether the interruption is slight or considerable, never omit one comma and leave the other. There is no defense for such punctuation as

Marjorie's husband, Colonel Nelson paid us a visit yesterday.

or

My brother you will be pleased to hear, is now in perfect health.

Dates usually contain parenthetic words or figures. Punctuate as follows:

February to July, 1992

April 6, 1986

Wednesday, November 14, 1990

Note that it is customary to omit the comma in

6 April 1988

The last form is an excellent way to write a date; the figures are separated by a word and are, for that reason, quickly grasped.

A name or a title in direct address is parenthetic.

If, Sir, you refuse, I cannot predict what will happen.

Well, Susan, this is a fine mess you are in.

The abbreviations etc., i.e., and e.g., the abbreviations for academic degrees, and titles that follow a name are parenthetic and should be punctuated accordingly.

Letters, packages, etc., should go here.

Horace Fulsome, Ph.D., presided.

Rachel Simonds, Attorney

The Reverend Harry Lang, S.J.

No comma, however, should separate a noun from a restrictive term of identification.

Billy the Kid

The novelist Jane Austen

William the Conqueror

The poet Sappho

Although Junior, with its abbreviation Jr., has commonly been regarded as parenthetic, logic suggests that it is, in fact, restrictive and therefore not in need of a comma.

James Wright Jr.

Nonrestrictive relative clauses are parenthetic, as are similar clauses introduced by conjunctions indicating time or place. Commas are therefore needed. A nonrestrictive clause is one that does not serve to identify or define the antecedent noun.

The audience, which had at first been indifferent, became more and more interested.

In 1769, when Napoleon was born, Corsica had but recently been acquired by France.

Nether Stowey, where Coleridge wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, is a few miles from Bridgewater.

In these sentences, the clauses introduced by which, when, and where are nonrestrictive; they do not limit or define, they merely add something. In the first example, the clause introduced by which does not serve to tell which of several possible audiences is meant; the reader presumably knows that already. The clause adds, parenthetically, a statement supplementing that in the main clause. Each of the three sentences is a combination of two statements that might have been made independently.

The audience was at first indifferent. Later it became more and more interested.

Napoleon was born in 1769. At that time Corsica had but recently been acquired by France.

Coleridge wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner at Nether Stowey. Nether Stowey is a few miles from Bridgewater.

Restrictive clauses, by contrast, are not parenthetic and are not set off by commas. Thus,

People who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.

Here the clause introduced by who does serve to tell which people are meant; the sentence, unlike the sentences above, cannot be split into two independent statements. The same principle of comma use applies to participial phrases and to appositives.

People sitting in the rear couldn't hear, (restrictive)

Uncle Bert, being slightly deaf, moved forward, (non-restrictive)

My cousin Bob is a talented harpist, (restrictive)

Our oldest daughter, Mary, sings, (nonrestrictive)

When the main clause of a sentence is preceded by a phrase or a subordinate clause, use a comma to set off these elements.

Partly by hard fighting, partly by diplomatic skill, they enlarged their dominions to the east and rose to royal rank with the possession of Sicily.

4. Place a comma before a conjunction introducing an independent clause.

The early records of the city have disappeared, and the story of its first years can no longer be reconstructed.

The situation is perilous, but there is still one chance of escape.

Two-part sentences of which the second member is introduced by as (in the sense of "because"), for, or, nor, or while (in the sense of "and at the same time") likewise require a comma before the conjunction.

If a dependent clause, or an introductory phrase requiring to be set off by a comma, precedes the second independent clause, no comma is needed after the conjunction.

The situation is perilous, but if we are prepared to act promptly, there is still one chance of escape.

When the subject is the same for both clauses and is expressed only once, a comma is useful if the connective is but. When the connective is and, the comma should be omitted if the relation between the two statements is close or immediate.

I have heard the arguments, but am still unconvinced.

He has had several years' experience and is thoroughly competent.

5. Do not join independent clauses with a comma.

If two or more clauses grammatically complete and not joined by a conjunction are to form a single compound sentence, the proper mark of punctuation is a semicolon.

Mary Shelley's works are entertaining; they are full of engaging ideas.

It is nearly half past five; we cannot reach town before dark.

It is, of course, equally correct to write each of these as two sentences, replacing the semicolons with periods.

Mary Shelley's works are entertaining. They are full of engaging id

eas.

It is nearly half past five. We cannot reach town before dark.

If a conjunction is inserted, the proper mark is a comma. (Rule 4.)

Mary Shelley's works are entertaining, for they are full of engaging ideas.

It is nearly half past five, and we cannot reach town before dark.

A comparison of the three forms given above will show clearly the advantage of the first. It is, at least in the examples given, better than the second form because it suggests the close relationship between the two statements in a way that the second does not attempt, and better than the third because it is briefer and therefore more forcible. Indeed, this simple method of indicating relationship between statements is one of the most useful devices of composition. The relationship, as above, is commonly one of cause and consequence.

Note that if the second clause is preceded by an adverb, such as accordingly, besides, then, therefore, or thus, and not by a conjunction, the semicolon is still required.

I had never been in the place before; besides, it was dark as a tomb.

An exception to the semicolon rule is worth noting here. A comma is preferable when the clauses are very short and alike in form, or when the tone of the sentence is easy and conversational.

Man proposes, God disposes.

The gates swung apart, the bridge fell, the portcullis was drawn up.

I hardly knew him, he was so changed.

Here today, gone tomorrow.

6. Do not break sentences in two.

In other words, do not use periods for commas.

I met them on a Cunard liner many years ago. Coming home from Liverpool to New York.

She was an interesting talker. A woman who had traveled all over the world and lived in half a dozen countries.

In both these examples, the first period should be replaced by a comma and the following word begun with a small letter.

It is permissible to make an emphatic word or expression serve the purpose of a sentence and to punctuate it accordingly:

Again and again he called out. No reply.

The writer must, however, be certain that the emphasis is warranted, lest a clipped sentence seem merely a blunder in syntax or in punctuation. Generally speaking, the place for broken sentences is in dialogue, when a character happens to speak in a clipped or fragmentary way.

Rules 3, 4, 5, and 6 cover the most important principles that govern punctuation. They should be so thoroughly mastered that their application becomes second nature.

7. Use a colon after an independent clause to introduce a list of particulars, an appositive, an amplification, or an illustrative quotation.

A colon tells the reader that what follows is closely related to the preceding clause. The colon has more effect than the comma, less power to separate than the semicolon, and more formality than the dash. It usually follows an independent clause and should not separate a verb from its complement or a preposition from its object. The examples in the lefthand column, below, are wrong; they should be rewritten as in the righthand column.

Your dedicated whittler requires: a knife, a piece of wood, and a back porch.

Your dedicated whittler requires three props: a knife, a piece of wood, and a back porch.

Understanding is that penetrating quality of knowledge that grows from: theory, practice, conviction, assertion, error, and humiliation.

Understanding is that penetrating quality of knowledge that grows from theory, practice, conviction, assertion, error, and humiliation.

Join two independent clauses with a colon if the second interprets or amplifies the first.

But even so, there was a directness and dispatch about animal burial: there was no stopover in the undertaker's foul parlor, no wreath or spray.

A colon may introduce a quotation that supports or contributes to the preceding clause.

The squalor of the streets reminded her of a line from Oscar Wilde: "We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars."

The colon also has certain functions of form: to follow the salutation of a formal letter, to separate hour from minute in a notation of time, and to separate the title of a work from its subtitle or a Bible chapter from a verse.

Dear Mr. Montague:

departs at 10:48 P.M.

Practical Calligraphy: An Introduction to Italic Script

Nehemiah 11:7

8. Use a dash to set off an abrupt break or interruption and to announce a long appositive or summary.

A dash is a mark of separation stronger than a comma, less formal than a colon, and more relaxed than parentheses.

His first thought on getting out of bed—if he had any thought at all—was to get back in again.

The rear axle began to make a noise—a grinding, chattering, teeth-gritting rasp.

The increasing reluctance of the sun to rise, the extra nip in the breeze, the patter of shed leaves dropping—all the evidences of fall drifting into winter were clearer each day.

Use a dash only when a more common mark of punctuation seems inadequate.

Her father's suspicions proved well-founded—it was not Edward she cared for—it was San Francisco.

Her fathers suspicions proved well-founded. It was not Edward she cared for, it was San Francisco.

Violence—the kind you see on television—is not honestly violent—there lies its harm.

Violence, the kind you see on television, is not honestly violent. There lies its harm.

9. The number of the subject determines the number of the verb.

Words that intervene between subject and verb do not affect the number of the verb.

The bittersweet flavor of youth—its trials, its joys, its adventures, its challenges— are not soon forgotten.

The bittersweet flavor of youth—its trials, its joys, its adventures, its challenges —is not soon forgotten.

A common blunder is the use of a singular verb form in a relative clause following "one of…" or a similar expression when the relative is the subject.

One of the ablest scientists who has attacked this problem

One of the ablest scientists who have attacked this problem

One of those people who is never ready on time

One of those people who are never ready on time

Use a singular verb form after each, either, everyone, everybody, neither, nobody, someone.

Everybody thinks he has a unique sense of humor.

Although both clocks strike cheerfully, neither keeps good time.

With none, use the singular verb when the word means "no one" or "not one."

None of us are perfect.

None of us is perfect.

A plural verb is commonly used when none suggests more than one thing or person.

None are so fallible as those who are sure they're right.

A compound subject formed of two or more nouns joined by and almost always requires a plural verb.

The walrus and the carpenter were walking close at hand.

But certain compounds, often cliches, are so inseparable they are considered a unit and so take a singular verb, as do compound subjects qualified by each or every.

The long and the short of it is…

Bread and butter was all she served.

Give and take is essential to a happy household.

Every window, picture, and mirror was smashed.

A singular subject remains singular even if other nouns are connected to it by with, as well as, in addition to, except, together with, and no less than.

His speech as well as his manner is objectionable.

A linking verb agrees with the number of its subject.

What is wanted is a few more pairs of hands.

The trouble with truth is its many varieties.

Some nouns that appear to be plural are usually construed as singular and given a singular verb.

Politics is an art, not a science.

The Republican Headquarters is on this side of the tracks

.

But

The general's quarters are across the river.

In these cases the writer must simply learn the idioms. The contents of a book is singular. The contents of a jar may be either singular or plural, depending on what's in the jar— jam or marbles.

10. Use the proper case of pronoun.

The personal pronouns, as well as the pronoun who, change form as they function as subject or object.

Will Jane or he be hired, do you think?

The culprit, it turned out, was he.

We heavy eaters would rather walk than ride.

Who knocks?

Give this work to whoever looks idle.

In the last example, whoever is the subject oHooks idle; the object of the preposition to is the entire clause whoever looks idle. When who introduces a subordinate clause, its case depends on its function in that clause.

Virgil Soames is the candidate whom we think will win.

Virgil Soames is the candidate who we think will win. [We think he will win.]

Virgil Soames is the candidate who we hope to elect.

Virgil Soames is the candidate whom we hope to elect. [We hope to elect him. ]

A pronoun in a comparison is nominative if it is the subject of a stated or understood verb.

Sandy writes better than I. (Than I write.)

In general, avoid "understood" verbs by supplying them.

I think Horace admires Jessica more than I.

I think Horace admires Jessica more than I do.

Polly loves cake more than me.

Polly loves cake more than she loves me.

The objective case is correct in the following examples.

The ranger offered Shirley and him some advice on campsites.

They came to meet the Baldwins and us.

Let's talk it over between us, then, you and me.

Whom should I ask?

A group of us taxpayers protested.

Us in the last example is in apposition to taxpayers, the object of the preposition of. The wording, although grammatically defensible, is rarely apt. "A group of us protested as taxpayers" is better, if not exactly equivalent.

Charlotte's Web

Charlotte's Web Stuart Little

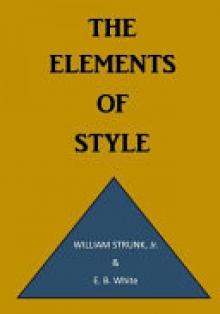

Stuart Little The Elements of Style

The Elements of Style Here Is New York

Here Is New York The Trumpet of the Swan

The Trumpet of the Swan Essays of E. B. White

Essays of E. B. White Writings from the New Yorker 1925-1976

Writings from the New Yorker 1925-1976 Letters of E. B. White

Letters of E. B. White